A weld can be created either as an individual spot or a seam weld.

The laser output that creates these welds can be achieved in one of two ways:

A pulsed laser produces a series of pulses, discrete packets of energy, at a certain pulse width and frequency until stopped. The “pulsed” descriptor refers to a laser that can produce a peak power that is greater than its average power.

A continuous wave (CW) laser produces extended output – the laser remains on continuously until stopped.

For example, a 25 W pulsed Nd:YAG laser can produce peak powers of up to 5 kW for a few milliseconds. This means it can produce a spot weld that would require a CW laser sized at 5 kW! With pulsed lasers a seam weld is created by a series of overlapping spot welds. For a continuous weld the laser remains on for the duration of the seam. A CW laser can also produce discrete pulses of laser light – known as gated or modulated output. In this case the CW laser peak power does not exceed the laser’s rated average power.

An Nd-YAG laser operates only in pulsed mode

Diode lasers operate in continuous wave

Fiber lasers can operate in both modes.

Choosing when to use pulsed, continuous wave, or modulated output is determined by the specific application. Spot welding typically uses pulsed operation. For seam welding, the selection is made based on heat input and cycle time. For instance, when seam welding an implantable device, a pulsed laser is used to minimize heat input and maintain a uniform weld around a complex geometry with varying welding speeds. In contrast, for airbag initiators, welding at high speed using CW operation is

Laser welding does not operate on the same principles as other types of welding like TIG, MIG, MAG,..

Laser welding uses a beam of light, instead of electricity, to join two pieces of metal together through a melting and cooling process.

Another key difference with laser welding is the intensity and ability to focus the heat source: the laser. The much higher, focused heat than, say, the electricity of a MIG welder or TIG welder, means that the weld occurs much more quickly. What’s more, the ability to narrowly pinpoint the weld area leads to much greater precision and more accurate and attractive weld joints.

What does this mean for you?

- Higher speeds: till 10x faster than MIG welding, and till 40x faster than TIG welding.

- Minimal/no finishing: The accuracy of the laser welding process means that little to no grinding or finishing is needed.

- Visually superior: Laser welding is ideal for straight line joints in furniture and other consumer products, since there is a much smaller heat-affected zone and a much tighter weld.

- Greater strength: A smaller heat-affected zone also means less weakening of the material.

So when wouldn’t you want to use laser welding? Thicker materials and parts where the weld joint construction does not allow the fit-up to be consistently maintained generally are not good candidates for laser welding.

Laser welding can be divided into the following processes:

Heat conduction welding and Keyhole (deep penetration) welding

Fiber laser welding is a high power density process that provides a unique welding capability to maximize penetration with minimal heat input. The weld is formed as the intense laser light rapidly heats the material – typically in fractions of milliseconds. There are two types of welds, based on the power density contained within the focus spot size: conduction modeand penetration/keyhole mode. A third type named as transition keyhole mode is the combination of the conduction mode and penetration/keyhole mode.

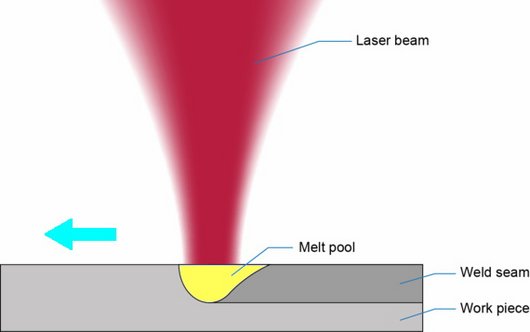

Conduction mode laser welding

Conduction mode welding is performed at low energy density, typically around 0.5 MW/cm², forming a weld nugget that is shallow and wide. The heat to create the weld into the material occurs by conduction from the surface. Typically this can be used for applications that require an aesthetic weld or when particulates are a concern, such as certain battery sealing applications.

Heat conduction welding is a laser welding method that features a low power output laser beam. This makes for a penetration depth of no more than 1 to 2 mm. With the ability to handle a relatively wide power range, heat conduction welding can be adjusted to the ideal power level, and the shallow penetration makes it possible to weld materials that are susceptible to heat effects under optimal conditions.

This welding type is used for butt joints, lap joints, and other welding applications for thin plates, and can also be used for welding hermetic seals and other seals. Heat conduction welding is also suitable for volatile alloys such as magnesium and zinc, for which keyhole (deep penetration) welding is not suitable.

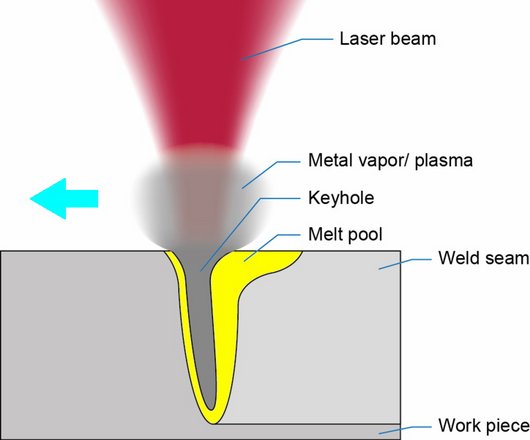

Transition mode laser welding

Transition mode laser welding occurs at medium power density, around 1 MW/cm2, and results in more penetration than conduction mode due to the creation of what is known as the “keyhole.” The keyhole is a column of vaporized metal that extends into the material; its diameter is much smaller than the weld width and is sustained against the forces of the surrounding molten material by vapor pressure. The depth of the keyhole into the material is controlled by power density and time. Because the optical density of the keyhole is low it acts as a conduit to deliver the laser power into the material.

Keyhole mode laser welding or penetration mode laser welding

Keyhole or penetration mode welding – Increasing the peak power density beyond 1.5MW/cm2 shifts the weld to keyhole mode, which is characterized by deep narrow welds with an aspect ratio greater than 1.5. The penetration depth rapidly increases when the peak power density is beyond 1 MW/cm2, transitioning the weld mode from conduction to keyhole/penetration welding.

Penetration or keyhole mode welding is characterized by narrow welds. This direct delivery of laser power into the material maximizes weld depth and minimizes the heat into the material, reducing the heat affected zone and part distortion. In this keyhole mode, the weld can be either completed at very high speeds – in excess of 500mm per second with small penetration typically under 0.5 mm – or at lower speed, with deep penetration up to 12 mm.

Keyhole welding (deep penetration welding) uses a high power output laser beam for high-speed welding. The narrow, deep penetration allows for uniform welding of internal structures. Because the heat-affected zone is very small, distortion of the base material, due to the heat from the welding, will be minimized.

This method is suitable for applications requiring deep penetration or when welding multiple base materials stacked together (including for butts, corners, Ts, laps, and flange joints).

Laser Welding Process Parameters

The key to success

Power density

Power density is one of the most critical parameters in laser processing. With a higher power density, the surface layer can be heated to the boiling point in the microsecond time range, resulting in a large amount of vaporization.

Therefore, high power density is advantageous for material removal processing such as punching, cutting, and engraving. For lower power densities, the surface temperature reaches the boiling point and takes several milliseconds. Before the surface layer is vaporized, the bottom layer reaches the melting point, and it is easy to form a good fusion weld.

Therefore, in conduction laser welding, the power density is in the range of 10^4~10^6W/CM^2.

Laser pulse waveform

Laser pulse waveforms are an important issue in laser welding, especially for sheet welding. When a high-intensity laser beam is incident on the surface of the material, the metal surface will be reflected by 60 to 98% of the laser energy and the reflectivity will vary with the surface temperature. During a laser pulse action, the metal reflectivity changes greatly.

Laser pulse width

Pulse width is one of the important parameters of pulse laser welding. It is an important parameter that is different from material removal and material melting, and is also a key parameter that determines the cost and volume of processing equipment.

The effect of the defocus amount on the weld quality

Laser welding usually requires a certain amount of defocus because the power density at the center of the spot at the laser focus is too high and it is easy to evaporate into holes. The power density distribution is relatively uniform across the planes exiting the laser focus.

There are two ways of defocusing: positive defocusing and negative defocusing.

The focal plane is located above the workpiece for positive defocusing, and vice versa for negative defocus. According to the theory of geometric optics, when the distance between the positive and negative defocus planes and the welding plane are equal, the power density on the corresponding plane is approximately the same, but the shape of the molten pool obtained is actually different. In the case of negative defocusing, a greater penetration can be obtained, which is related to the formation of the molten pool.

Experiments have shown that the laser heating 50~200us material begins to melt, forming liquid phase metal and partially vaporizing, forming high pressure steam, and spraying at a very high speed, emitting dazzling white light. At the same time, the high concentration vapor moves the liquid metal to the edge of the bath and forms a depression in the center of the bath.

When negative defocusing, the internal power density of the material is higher than the surface, and it is easy to form a stronger melting and vaporization, so that the light energy is transmitted to the deeper part of the material. Therefore, in practical applications, when the penetration depth is required to be large, negative defocusing is used; when welding thin materials, positive defocusing is preferred.

Welding speed

The speed of the welding speed will affect the heat input per unit time. If the welding speed is too slow, the heat input is too large, causing the workpiece to burn through. If the welding speed is too fast, the heat input amount is too small, causing the workpiece can’t be welded well.

Systèmes de soudage laser industriels

Le soudage au laser industriel a eu un impact dramatique dans l'industrie de la machine-outil au fil des ans et est devenu la réponse à de nombreux problèmes provoqués par les méthodes de soudage traditionnelles. De nombreuses entreprises métallurgiques se sont tournées vers le soudage par points laser et le soudage par cordon laser en raison de ces avantages. L'automatisation, les vitesses de soudage élevées et le traitement sans contact aident les utilisateurs de soudage laser à obtenir très rapidement des avantages économiques.

Étant donné que le soudage au laser produit une énergie pure et concentrée, il crée des soudures plus profondes tout en laissant un rendement de production élevé. C'est l'une des nombreuses raisons pour lesquelles les systèmes de soudage par points et de soudure au laser sont utilisés dans la fabrication de cette industrie. Les articles que nous utilisons tous les jours dans nos gadgets, appareils électroniques et pièces sont passés par la technologie de soudage au laser au cours de leur production.

Soudage par points au laser et soudage au laser

Le soudage par points au laser, le soudage par cordon au laser et le soudage direct sont des applications très utiles et légèrement différentes de la technologie de soudage au laser. Le soudage par points et par cordon au laser fait référence aux fonctions de soudage appliquées à un seul point ou le long d'une ligne. En réglant un système de soudage laser sur une géométrie de soudage à grande vitesse et extrêmement étroite, le soudeur laser peut produire un soudage par points extrêmement fin. En outre, vous pouvez régler le système pour souder en mode onde continue, en soudant avec plusieurs kilowatts de puissance. La vitesse laser idéale pour les projets de soudage par points ou par cordon varie en fonction du modèle de laser particulier, du réglage de la puissance du laser et du matériau à souder au laser.